Exploring Coyote

Understanding Coyote’s Task-based Programming Model

Coyote’s task based programming model allows developers to express the concurrency of their programs using the familiar and heavily used .NET TPL framework. Developers use Coyote’s variant of the Task class, which acts as a very thin wrapper over .NET Tasks in production but allows Coyote to carefully and systematically explore the different concurrent schedules during testing. This allows developers to leverage Coyote’s testing capabilities without changing how they design and structure their applications.

We’ll explore Coyote’s task based programming model in this article. You should have an intuitive understanding of how it works after going through the examples and discussion below. It will not talk about how to test interesting safety and liveness properties through Coyote but will instead focus on the mechanics of how Coyote explores the concurrency of programs written using .NET TPL’s framework. This will give you a solid foundation to build upon which will help you later learn how to leverage Coyote to test safety and liveness properties of your application.

Before proceeding further, please spend a few minutes going through and reasoning about the behavior of the following program. Take out a piece of paper, or your favorite text editor and write down the various outputs you expect to see on the console in different runs of the following program.

1 public async Task Bar(string id)

2 {

3 Console.WriteLine($"Entering Bar {id}");

4 await Task.Run(() =>

5 {

6 Console.WriteLine($"Work in Bar {id}");

7 });

8 Console.WriteLine($"Exiting Bar {id}");

9 }

10

11 public async Task Foo(string id)

12 {

13 Console.WriteLine($"Entering Foo {id}");

14 await Bar(id);

15 Console.WriteLine($"Exiting Foo {id}");

16 }

17

18 public static void Main()

19 {

20 var task1 = Foo("1");

21 var task2 = Foo("2");

22

23 Console.WriteLine("Waiting");

24 Task.WaitAll(task1, task2);

25 }

If you’re done understanding the behavior of the above program, then continue reading.

This program spins off two tasks, each of which prints a message Work in Bar {id}, then waits for both of the tasks to complete and then exits. Different runs of the program can produce different outputs on the console. Here are 3 possible outputs:

Possible output 1

Entering Foo 1

Entering Bar 1

Entering Foo 2

Entering Bar 2

Work in Bar 1

Work in Bar 2

Waiting

Exiting Bar 1

Exiting Foo 1

Exiting Bar 2

Exiting Foo 2

Possible output 2

Entering Foo 1

Entering Bar 1

Work in Bar 1

Entering Foo 2

Exiting Bar 1

Entering Bar 2

Exiting Foo 1

Work in Bar 2

Exiting Bar 2

Waiting

Exiting Foo 2

Possible output 3

Entering Foo 1

Entering Bar 1

Work in Bar 1

Entering Foo 2

Exiting Bar 1

Entering Bar 2

Work in Bar 2

Exiting Foo 1

Exiting Bar 2

Waiting

Exiting Foo 2

Did you notice the first two lines in all three outputs above always have “Entering Foo 1” and “Entering Bar 1” as the first two lines. Will that always be the case? And why is that?

The program doesn’t hit a source of asynchrony till it hits the Task.Run statement in line 4. After it hits Task.Run, there are two concurrent control flows in the program whose outputs can be interleaved with each other. This is a minor and subtle but important point to keep in mind. If there was no Task.Run at line 4, there will be no asynchrony in the system and the system will always produce the following output. Having ‘async’ methods and using ‘await’ expressions in your code doesn’t introduce any asynchrony in your system - it just helps you write concise code to deal with the asynchrony. Methods like Task.Run, Task.Delay, Task.Yield, Task.When etc are the sources of asynchrony in your system. Coyote calls such statements ‘scheduling points’.

The only possible output if there was no Task.Run in the program

Entering Foo 1

Entering Bar 1

Work in Bar 1

Existing Bar 1

Exiting Foo 1

Entering Foo 2

Entering Bar 2

Work in Bar 2

Existing Bar 2

Existing Foo 2

Waiting

With the above important observation out of the way, let’s ask ourselves can interesting question.

Can you estimate the number of possible outputs the above program can result in?

Think hard.

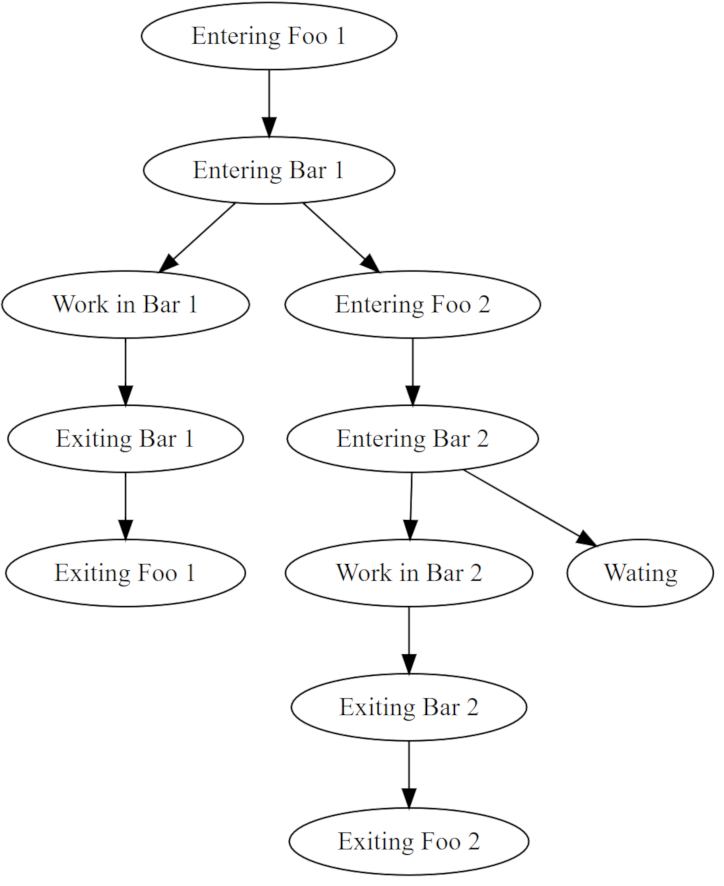

In order to better understand its behavior, let’s visualize the sources of asynchrony and different control flows in the program through the following diagram:

Each output to the console is a node in the diagram above. We see that up till Entering Bar {id}, there is only one control flow. Once we hit Task.Run, there are two control flows in the system, each of whose executions can interleave with each other. As soon as we hit more than one control flow, the possible inter-leavings increase manifold. The longer each control flow is, and the more the number of active control flows, the more possible inter-leavings we’ll have.

The above tiny program can in fact lead to 366 distinct outputs!

The number of possible inter-leavings in a tiny program was a humbling realization for me. Production programs are much longer and contain a much larger number of asynchronous operations which results in a huge state space. Systematic testing tools like Coyote can greatly increase your confidence in the correctness of your code as they explore the state space for you and verify the safety and liveness properties at each step.

Now that you have an understanding of what the above program does and the number of possible outputs, let’s switch to talking about how Coyote explores the concurrency of the above program.

Coyote makes a simplifying assumption which reduces the number of possible schedules it has explore thus helping it to scale to test large production systems with many thousands of lines of code. Coyote doesn’t explore inter-leavings at each possible instruction; it instead runs a control flow continuously till it hits a scheduling point and only explores the inter-leavings at the boundaries of these scheduling points. This results in a reduced coverage of the number of possible inter-leavings but allows it to scale much better and still catch a large number of interesting bugs. As an example, a number of subtle bugs in production programs happen when one task changes the state of an external resource, say, a database which interleaves with another task reading the state of the same row in the database. Such reads and writes are often done through asynchronous read and write SDK methods and exploring the inter-leavings at these scheduling points catches a lot of interesting bugs.

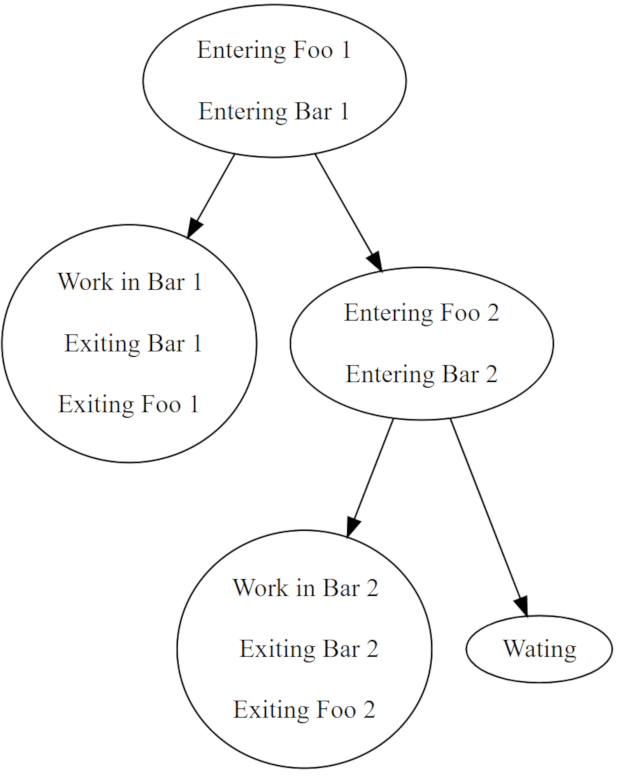

To make things concrete, Coyote explores a graph which has the following shape:

As you can see, Coyote always executes a bunch of instructions together, with each such grouping called a step. The number of active control flows in the system remains the same but the length of each control flow is reduced due to grouping of instructions which always execute together. This reduces the number of distinct possible outputs to 8. This trade-off is often worth it as it allows the testing to scale to larger programs while still catching interesting bugs which surface due to inter-leavings at the boundaries of the scheduling points. It does miss bugs which are caused by inter-leavings of instructions within boundaries of the scheduling points. Coyote provides tools through which developers can introduce artificial scheduling points to break apart the groups and increase the number of explored inter-leavings.

Let’s study how Coyote explores the concurrency of the above program step-by-step. We’ll paste the program again for easy reference.

1 public async Task Bar(string id)

2 {

3 Console.WriteLine($"Entering Bar {id}");

4 await Task.Run(() =>

5 {

6 Console.WriteLine($"Work in Bar {id}");

7 });

8 Console.WriteLine($"Exiting Bar {id}");

9 }

10

11 public async Task Foo(string id)

12 {

13 Console.WriteLine($"Entering Foo {id}");

14 await Bar(id);

15 Console.WriteLine($"Exiting Foo {id}");

16 }

17

18 public static void Main()

19 {

20 var task1 = Foo("1");

21 var task2 = Foo("2");

22

23 Console.WriteLine("Waiting");

24 Task.WaitAll(task1, task2);

25 }

Coyote continues executing the control flow starting when the Main method begins execution till it hits the first scheduling point at line 4. At line 4, there are two control flows in the system.

Control flows: [20-13-4, 21]

Output

Entering Foo 1

Entering Bar 1

20-13-4 refers to the control flow which will resume execution from line 4 and was reached by invoking Foo("1") at line 20, followed by invoking Bar("1") at line 13 and finally hitting Task.Run at line 4. The second control flow will resume execution on line 21 by invoking Foo("2"). Coyote will explore the schedules resulting from choosing either one of those. For illustration, let’s study the run where Coyote chooses to run the control flow at line 21. That control flow will once again run till it hits a scheduling point, or finishes execution. In our program above, it will hit the scheduling point at line 4 again, this time reached through another series of calls.

Coyote chose 21

Control flows: [20-13-4, 21-13-4, 23]

Output

Entering Foo 1

Entering Bar 1

Entering Foo 2

Entering Bar 2

Coyote now has three possible control flow choices. It can execute the control flow which will result in Work in Bar 1, or one which will result in Work in Bar 2 or control flow at line 23 which will print Waiting.

Let’s assume Coyote chooses 21-13-4

Coyote chose 21-13-4

Control flows: [20-13-4, 23]

Output

Entering Foo 1

Entering Bar 1

Entering Foo 2

Entering Bar 2

Work in Bar 2

Exiting Bar 2

Exiting Foo 2

Coyote executes the Task which prints Work in Bar 2 but it then continues till it hits another scheduling point or finishes. This task then prints Exiting Bar 2 followed by Exiting Foo 2 and finishes execution.

Coyote now again picks a control flow to execute. Let’s assume it picks 23

Coyote chose 23

Control flows: [20-13-4, 24(waiting)]

Output

Entering Foo 1

Entering Bar 1

Entering Foo 2

Entering Bar 2

Work in Bar 2

Exiting Bar 2

Exiting Foo 2

Waiting

The program prints Waiting and hits another scheduling point, Task.Wait which is added to the list of control flows. This particular control flow however is in a waiting state and cannot be executed till 20-13-4 finishes. Coyote thus only has one choice which is to execute 20-13-4

Coyote chose 20-13-4

Control flows: [24]

Output

Entering Foo 1

Entering Bar 1

Entering Foo 2

Entering Bar 2

Work in Bar 2

Exiting Bar 2

Exiting Foo 2

Waiting

Work in Bar 1

Exiting Bar 1

Exiting Foo 1

After control flow 20-13-4 finishes execution, 24 is unblocked and is the only remaining control flow. Coyote executes it and the program terminates.

The above was just one possible serialization of the program. Coyote executes the program many times, each time exploring a different serialization of the program. It encourages developers to sprinkle their code with Assert statements, or check invariants at the end of each run which allows them to be confident their program does not violate any safety conditions in the many different possible serializations it explores. It also provides tools through which developers can express liveness conditions which test the program eventually makes progress. We’ll explore that feature in another article.

To summarize, this article explored the mechanics of how Coyote explores the concurrency encoded in programs written using .NET’s TPL framework and worked through a detailed example to help you build an intuitive mental model of how it works under the hood.